It can take a village to feed hungry kids in schools

It can take a village to feed hungry kids in schools

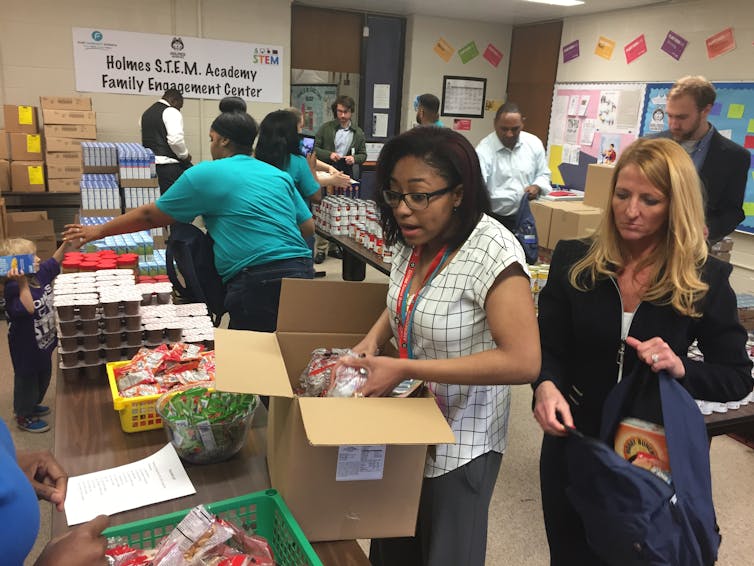

Kathleen Payton/Food Bank of Eastern Michigan, CC BY-SA

Sarah Riggs Stapleton, University of Oregon

One in 6 American children faces hunger and 3 out of 4 teachers report regularly seeing hungry kids in their classrooms. In response, school meals make up a large fraction of federal food assistance.

The National School Lunch Program is the second-largest federal food assistance program, serving 30.4 million children. It is complemented by the School Breakfast Program, the Afterschool Snack Service and the Summer Food Service Program. Though these programs are essential, they are not enough.

On a local scale, organizations such as food banks assist food-insecure children and families, but their work within schools is typically limited. In my roles as a researcher of food in schools and as a food bank board member, I often see opportunities for more collaboration between schools and communities to help fill the gaps in feeding kids whose families face economic hardship.

Local efforts are limited

In some communities, food banks and K-12 schools already work together as partners.

One way this occurs is through backpack programs that give students easily prepared foods, like boxed macaroni and cheese and canned beans, for the weekend. Backpack programs, such as those in Northeast Michigan and Arlington, Virginia, are highly local.

Often these initiatives exist because someone, such as a high school teacher I collaborated with on a study, Melissa Washburn, sees a need and reaches out to local food banks for support. Washburn, a health teacher at a public high school in Lansing, Michigan, partnered with a nearby food bank to initiate a backpack program that delivered shelf-stable items. Wanting to improve the quality of the food in the packs, Washburn secured grants from a local nonprofit and the schools’ alumni association to include locally sourced fruits and vegetables.

Food pantries located in schools are another source of support for hungry students and their families. These efforts also often depend on one or a handful of dedicated people who see a need and amass volunteers for the task.

Local efforts are important and should be the norm rather than the exception. School-based food pantries and weekend backpack programs should be a routine feature at all public schools.

Bringing in the village

While school food pantries and backpack programs are important, we need to welcome more ideas to the table to feed children in schools. Because funding for public education is limited and teachers are overextended, the village needs to help support these endeavors.

There are countless models for marshaling communities to feed students. Service organizations, faith-based groups and local clubs can step in to help.

Food banks, in particular, are in excellent positions to foster connections between schools and these groups. For example, a network of churches in Junction City, Oregon, works with the food bank to supply items, such as peanut butter, for backpack programs in local schools.

Partnerships between businesses and nonprofits, such as the Cereal for Youth program in Lane County, Oregon, are another model. This program brings three local businesses together with the food bank to provide free high-quality granola to kids 18 years and under in schools or afterschool programs.

Another important initiative is lobbying for better federal or state school food assistance. In Oregon, nonprofits, food banks and other organizations have formed the Hunger-Free Schools Coalition to encourage state legislators to make Oregon the first state to provide universal free school meals.

Food can also provide a gateway to building community in and around schools. For example, our food bank nutrition educator teaches family cooking classes at a local elementary school. Free evening or weekend meals for school communities with food provided by food banks and partners are another possibility.

Schools are places where food assistance can have great impact on vulnerable members of society. Community organizations, businesses and food assistance agencies all have roles to play in this effort.![]()

Sarah Riggs Stapleton, Assistant Professor, Education Studies, College of Education, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We should serve kids food in school, not shame

We should serve kids food in school, not shame

For the past several years, reports have surfaced about the “shaming” of students for outstanding school meal debts. These students, often from low-income families, are being publicly humiliated because they have unpaid debt in their school meal accounts. Policies that shame students can include stamping on children’s hands or arms, taking their food away and dumping it in the trash or giving them stigmatized cold, partial meals in lieu of the regular hot lunch.

As an education researcher who studies food in schools, I believe it’s our duty in schools to treat students with dignity and compassion. Moreover, access to food is a basic human need and should be considered a right – regardless of income. The best way to combat meal debt shame in U.S. public schools is to provide every student with free meals.

Addressing the problem

Public outcry about school meal shaming has sparked the creation of at least 30 GoFundMe campaigns organized by parents and teachers to pay remaining balances on student accounts. One school volunteer has even created a nonprofit to help pay for kids’ meals.

New Mexico, California and Texas have begun crafting legislation to prohibit withholding food from students or to ban meal debt shaming altogether.

All of this has led to the USDA issuing a memorandum for school districts to clearly communicate their policies for meal fees to parents and guardians. However, the policy only suggests guidelines and provides no solid prohibitions against the shaming of students.

In a more extensive attempt to address the issue, the Anti-Lunch Shaming Act of 2017 has been introduced in the House and Senate by a bipartisan group of lawmakers. This bill would ban the shaming of students, prohibit the throwing away of food after it’s been served, and require districts to communicate directly with parents and guardians about school food debts.

Schools’ ethical responsibility

While these measures are steps in the right direction, addressing lunch shaming is treating a symptom rather than the underlying disease. All students need to eat every day, regardless of the funds available to them.

Given that we provide free schooling for all students in the country – regardless of family income – perhaps we should reexamine our societal norms around feeding them as well. Sociologist Janet Poppendieck suggests in her 2010 book “Free for All” that we can and should provide free food to all students in our schools.

This move is not unprecedented: Sweden, Finland and Estonia provide free food to all students in public schools, regardless of income. (Finland’s education system is considered by many to be the best in the world, and Estonia has been rated in the top 10.)

Why are we so reluctant to feed all students in the U.S.?

Prior to the 20th century, schools did not provide any kind of food for students: Students typically went home for lunch or brought their own food. This separation between eating and learning may have been a relic of the mind-body duality from Descartes, which assumes that schools are for disembodied minds. In fact, school meals did not begin until the early 20th century Progressive Era, when charities, women’s groups and PTAs provided supplemental lunches to children in need. American schools began offering meals to students on a wide-scale basis as part of the New Deal program, partly (or perhaps mostly) to help provide markets for agricultural surpluses.

The need

Today there’s unprecedented need for students in the U.S. to be fed. For the first time in our history, the majority of students in U.S. schools are living in poverty. Many of these students are food-insecure and dependent on the food provided in schools, sometimes as the only meals they eat daily.

Over 31 million students in the U.S. rely on free or reduced-price meals through the National School Lunch Program. Through the program, free meals are available to families who make under US$31,500 for a household of four, while reduced-price lunches are available to families who make just below $45,000 for a family of four.

However, the income cutoffs for these programs don’t take into account the wide variation in cost of living across the country. Moreover, Poppendieck has reflected that a family making just enough to be ineligible for free lunches may struggle as much as a family who qualifies.

The application for free/reduced lunches itself can be a barrier for students who might otherwise be eligible. Families may be worried about bringing attention to undocumented status through filling out an application, or they may simply be unclear about the process.

Families may also be ashamed to ask for help. For example, a teacher with whom I partnered in my research shared that though she experienced hunger as a child, her mother forbade her from accepting free meals at school. As a child, she didn’t understand why, but was nonetheless subject to her mother’s decisions.

In short, there are complicated nuances and challenges in understanding individual students’ food security. Shame is already a part of this picture. We shouldn’t be compounding it.

Addressing the need

The Summer Food Service Program, a partnership between the USDA, nonprofits and government agencies (including libraries), provides free meals for kids ages 2-18 during the summer months when public schools are not in session. In this program, all a child needs to do to be eligible for the food is to show up at the designated place and time. I believe that this model of providing free food to children and teens with no need for proof of eligibility should be used in our schools, too.

There have been some strides toward making free food for all students a reality. Thanks to the Community Eligibility Provision of the Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act of 2010, districts where at least 40 percent of students are served by benefit programs can choose to provide free food for all students. The federal government reimburses participating schools based on the percentages of students qualifying for benefit programs.

But this promising policy can lead to problems. For example, in the Portland, Oregon public schools, 12 schools lost their community eligibility status over the summer of 2017 because their qualifying student percentages declined.

What’s more, while the Community Eligibility Provision serves broadly low-income areas, it doesn’t address the increasing and perplexing nature of suburban poverty, where children from low-income backgrounds may be overlooked because of the affluence around them.

It’s simply not enough to provide free meals to some students, or to all students in some schools. While providing free meals to all public school students would be costly, given that we provide textbooks, facilities, teachers, special education services and other essentials required for schooling, how can we continue to omit food as an educational essential?

Meal debt shaming is a serious problem, but student hunger is even more so. It’s time to move aggressively to make free food available to all students, in all U.S. public schools. It’s the least we can do.![]()

Sarah Riggs Stapleton, Assistant Professor, Education Studies, College of Education, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.